Our brilliant guest blogger Dr Richard Read is back from 6 months in Europe and has written this enlightening review for us on Agnes Martin and Time-Piece at the Tate Modern.

In a six month trip to Europe I must have visited scores of art exhibitions in the UK, France and Italy. I don’t like to talk in terms of bests and favourites, as if the whole world had to be graded like a GDP, but what bubbles to the top of memory is a large retrospective exhibition of paintings by the American twentieth-century abstract artist Agnes Martin at Tate Modern, which is still on as I write. It still blows my socks off, if that’s the right term for such an intensely visual and contemplative experience of ‘low-powered’ art. (High and low powered are just different types of art, not value judgements.)

I already knew I was supposed to like her work, knew what it was supposed to look like and must have seen a real work or two by her across the globe, but I wasn’t expecting the reality. The reality. She’s supposed to have turned her back on one kind of reality:

“The modern world left her cold; in the stark New Mexico landscape she found a spiritual clarity unmarred by material entanglements. Daily life was Spartan. Though she liked classical music she never owned a stereo; nor did she have a television. She had no pets. One of her obituaries reported that when she died – in 2004 at 92 – she had not read a newspaper for 50 years. Two years before her death she allowed a persistent woman film-maker to shoot a documentary about her: it was entitled With My Back to the World. Leaving no survivors, she directed that her estate be used to fund a foundation for artists but insisted that it not bear her name.” 1

Of course turning your back on the modern world means turning your front somewhere else, in her case the New Mexico landscape and her studio abstracts. It so happened that I rushed to see this show on the Sunday before I returned to Australia and got to the Tate at about 3 pm. I was unaware at the time that a huge political work, ‘Time Piece’, in which a friend of mine was a key player, was taking place in the Turbine Hall, on the big concrete entrance slope of the gallery. I’ll return later to the issue of whether an activist engagement with the art political world can actually belong to the same category of art as Martin’s back and front-turning work based as it was on schizophrenic isolationism with Buddhist overtones. Hence her beautiful but alarming dictum:

“We have been very strenuously conditioned against solitude. To be alone is considered a grievous and dangerous condition. So I beg you to recall in detail any times when you were alone and discover your exact response to those times. I suggest to artists that you take every opportunity of being alone, that you give up having pets and unnecessary companions. You will find that the fear that we have been taught is not just one fear but many different fears. When you discover what they are they will be overcome. Most people have never been alone enough to feel these fears. But I suggest that people who like to be alone, who walk alone will perhaps be serious workers in the art field.”

Even more alarmingly she said that babies come into the world with a dagger in their hand called ego that they use to cut the world up to make a space in it for themselves. Although she adds that the infant’s interactions with its mothers take half of that murderous egotism away from them right from the start, her goal is for us to get rid of the rest of it and enter a permanent anti-egoic state. That’s against my current experience of a little grandson who radiates as much love on the world as he receives from it. He restores my faith in human nature, but I’ll return to the art squabble later.

Up there with her works on the third floor I had one of the most intense illusions of oneness with the universe ever. Here are three impressions from it, though it’s crazy and off-putting to post images from the internet with them, for nothing gets through.

Agnes Martin, Grey Stone, 1963

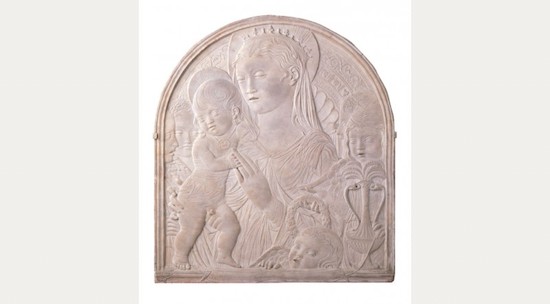

There was a six-foot square work called ‘Grey Stone’, 1963, which like so many of her works sported an unaccountable rift between means and effect. The means were a yellow and blue wash on an infinitely small grid of hand-drawn graphic lines. Step back and you have the undulating loveliness not of a skimming stone itself but of the surface of such a stone, as if it had been alluvially washed over millennia. The skin of the children in a bass-relief by Agostino di Duccio would be a parallel experience, but there the means and effect are at one with each other.

Agostino Di Duccio, Virgin and Child with Five Angels 1450-60

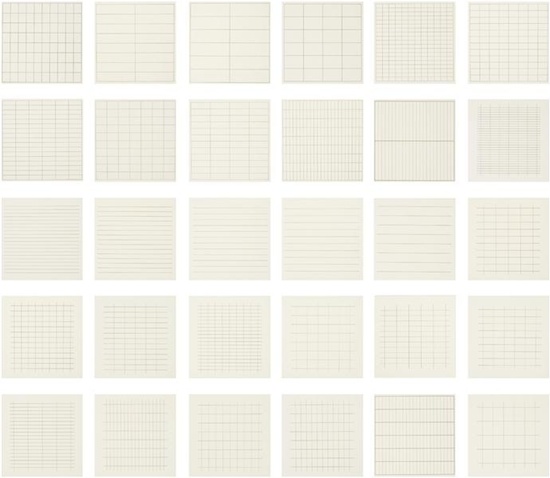

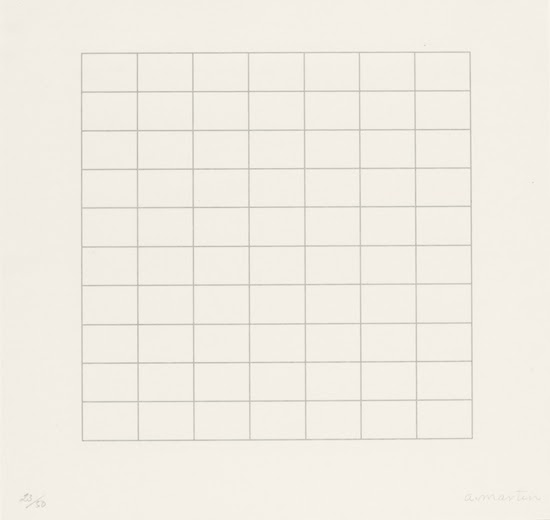

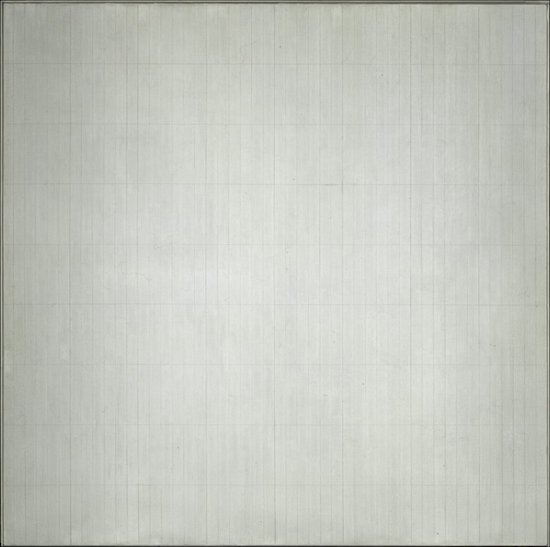

Agnes Martin, On a Clear Day, 1973

There was a corridor of initially unremarkable little prints called ‘On a clear day’ (is the link with Delorean’s book On a Clear Day You Can See General Motors accidental? No! The prints begin in 1972, the book is 1979.). They are ‘just’ grid patterns of the simplest and most uniform kind, printed with the assistance of machines ‘to straighten out her lines, which she said she could never paint straight enough’, but as each one passes before your mind the whole universe seems to take on a different structure. Would they work if they weren’t shown together? She said this of them: ‘These prints express innocence of mind. If you can go with them and hold your mind as empty and tranquil as they are and recognise your feelings at the same time you will realise your full response to this work’ (1975).

Agnes Martin, The Islands, 1979

Realising your full response to the works is the gist of the matter. When one of the Guardian critics moved past the ‘60s rooms ‘all the heat seems to leave the galleries’ for her. When she gets to the room given over to The Islands I-XII (1979) … a group of seven almost-white paintings … which the curators deem to be among her “most silent works”’ … I experienced them as something muffled, frustration and boredom in fierce competition to hurry me from the room.’ Oh dear! I think she’s missed something absolutely basic for which a placard in the gallery prepares you much better. It tells us that these works ‘invite concentrated looking over time in order to see their very fine lines and subtly nuanced surfaces.’ But this still isn’t it. These works, and these works together, are not about their surfaces but about finding our optional relationships with their after-images. Wherever you look your eyes push an area of grey around their surfaces that you cannot get away from, however adamantine their resistance as flat walls of paint. You’re in a subjective relationship with them and bring your life to them whether you want to or not, once you become aware of this optical relationship which knowledge alone drives away. They have to come alive because you and your eyes are. But if you never find this relationship they are going to stay dead. It requires the vigilant passivity that for her was a quasi-religious outlook on everything.

It’s this which makes it difficult to put her work in the same compartment as the oppositional art protest that was taking place unknown to me below. On the video clip which was the main record of this event (featured in an earlier Super Minimal posting), people spoke of the eeriness and beauty of staying up all night in the turbine hall after the graffiti had been written, the make-shift kitchens and toilets installed and the custodians resisted, but somehow that is letting politics and aesthetics fall into successive compartments. Where Martin turns her back on the corporate world (she was a schizophrenic for chrissake), a large part of these folks’ performance was engaging with police and gallery staff and creating the enormous wave of publicity which followed. There is something collectivist about Martin’s stance too, but as a sometimes Buddhist she believed that everything in existence has its purpose, even what reactionaries do, so render unto Caesar, political activism would seem impossible for her. The planning and agitating of the time-piece warriors, however, was hardly egotistical and was indeed exactly timed to coincide with ebb and flow of tides, finding its way back to a putative universal that way. Did what was happening on floor three and in the basement therefore belong to the same conceptual box called art? Probably not, but again, why choose?

References

1. Terry Castle, ‘Travels with My Mom’, London Review of Books, 29: 17, 16 August 2007, p. 13.