Please allow me to introduce myself. I am Dr Permangelo E. Regularis, curator and art agent for a small but significant stable of established and emerging Australian artists. I am proud to present them to you here – they are Nola Farman, Nora Fleming, Desirée de Kikk, Noel Farina, Victoria (Vicky) Versa, Flavia Dejour and Marco Smudge.

One of my artists, Desirée de Kikk, who is both a writer and performance artist has asked (dare I say demanded) to write our first blog. She insists that she has something rather urgent to bring to the attention of your readers – a matter of significance and pertinence to the state of contemporary art in West Australia – and beyond. It concerns the fact that the Art Gallery of Western Australia is planning to de-accession The Lift Project (by Nola Farman and Michael Brown) from its collection – an iconic artwork first shown in 1983, that has been acclaimed internationally (it received an award at Ars Electronica) and influenced a generation of West Australian artists.

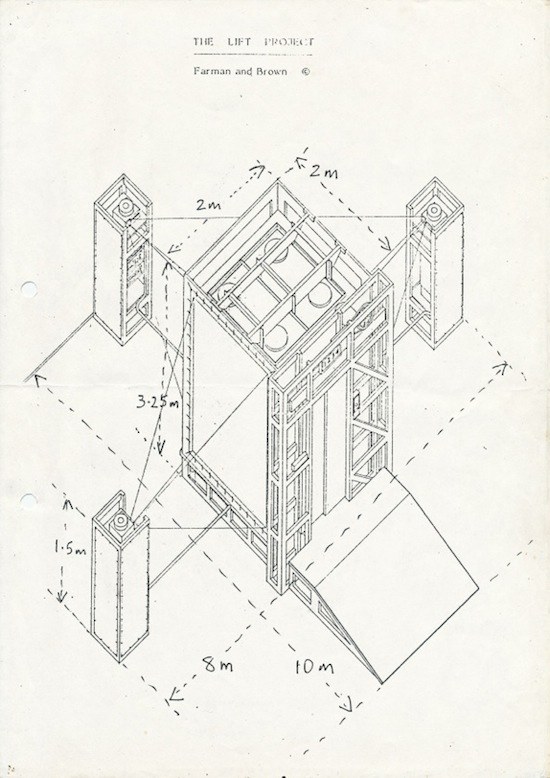

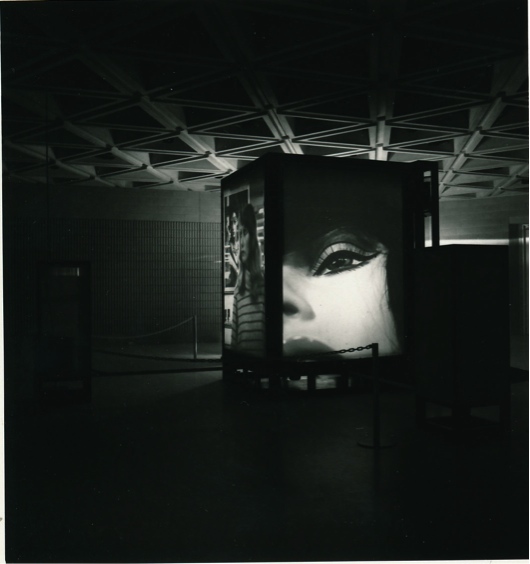

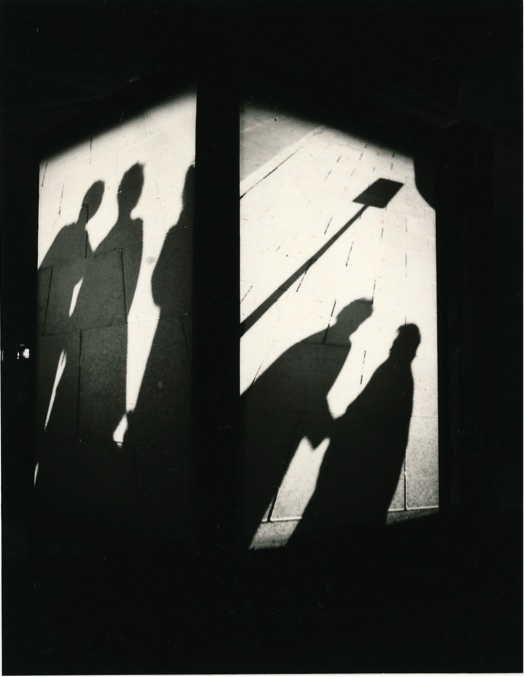

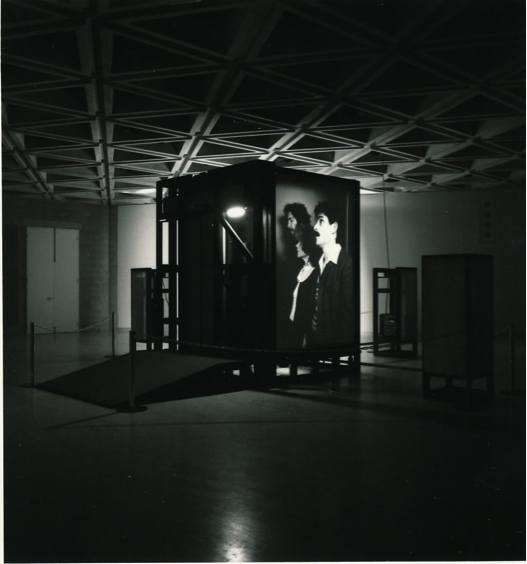

In Desirée’s words: ‘It has just come to my attention that the Art Gallery of Western Australia plans to de-accession an iconic artwork made by Nola Farman and Michael Brown in the early 1980s. After a brief conversation with Nola, I understand that the reasons given for this act of de-accessioning make it clear that the institutional memory of the Art gallery has faded with the change and passing of staff. It is now claimed that it takes several weeks to install the Lift. In fact with the use of an operating manual provided by the artists, Michael Brown (the designer of the piece and an award-winning industrial designer in his own right) tells me it takes only five days (or less) to assemble. It can then be demounted and packaged in one day. Once put together, upon installation, the Lift will then automatically switch itself on with the daily opening of the Gallery, set all its own systems to the ready and wait for the first lift rider to arrive, push the start button and open the sliding doors. It then swallows the rider and “transports” them in a tantalizing 10 minute experience of vertical travel! As I recall, it is like a kind of Tardis with an ever-expanding internal space – the space of fear, displacement and the imagination.

‘It is also claimed by the gallery, that the technology is outmoded and cannot be operated without being upgraded. Not true! The original system is functional and appropriate (even vital) in an artwork that is in essence a self-reflexive machine, tailored in an historic sense to its time and place. A dedicated computer coordinates the doors, lights, sound and images back-projected onto the walls by three slide projectors. In fact the old clunking sound at the change of slides was deliberately conceptualised as an integral element in the sound track – a reference to the machine. This exemplifies one theory of the lift phobia, that we have a terror of placing ourselves in the power of a machine. The sequence of this lift experience, traces an audio-visual passage through an anatomy of a phobia to a kind of epiphany or sense of “flooding viva”.

‘To complicate and deepen the experience, the Lift telephone, conventionally used to escape entrapment in the case of machine malfunction, in this case its audio sequence makes reference to a primal slip into the subconscious or a passage to Hell. As the late Jill Bradshaw wrote in the Lift catalogue, “… the lift telephone provides the passenger with the knowledge or information which will enable him/her to traverse the terrors of the psyche unscathed, just as the golden bough gave Aeneas immunity in the Underworld. Armed with this verbal talisman – the awareness of fears, anxieties and phobias which constitute the basis of the rites of passage – the traveller has the power to name and therefore to vanquish the perils encountered in the journey towards self-knowledge.” Jill writes on: “The lift is in a sense a journey and it is in a sense the shortest possible journey one can make and yet which can be psychologically the equivalent of a major displacement in time and space. Few people will remain unchanged by the experience of the lift-piece because of its manifest power to evoke the sequeilae of the rites of passage during a brief moment of displacement.”

‘This complex work was arguably one of first of its kind in Australia – even before early audio-visual systems were commonly used. To my mind it has a unique place in Australian art history – it is special for Western Australia. If anyone reading this blog was fortunate enough to have experienced this artwork in the 1980s (or even if you wish you had) I urge you to write to Jenepher Duncan, the Curator of Australian Art at the Art Gallery of Western Australia, to ask for at least one more viewing before the artwork is dismantled. Adding to this, I have heard that there is some discussion in Sydney of a large retrospective showing of the works of Nola Farman. The re-exhibition of The Lift project could be a significant West Australian contribution to such an event.

‘In the end, ideally, The Lift Project would be located in a collection. However its sheer size and the number of packages involved could be daunting for the conventional collector.’