Written by Richard Read

At the Art Gallery of Western Australia, we go downstairs, along a distant corridor and into a single room of the suitably nineteenth-century Centenary Galleries. The ‘Continental Shift’ exhibition is on until 5 February 2017, when the American paintings will move to the Ian Potter Gallery at The University of Melbourne to hang amongst a new set of Australian paintings.

The exhibition was accompanied by two teaching units, a level three undergraduate unit and an Honours seminar, both called ‘Colonization and Wilderness: Nineteenth-century American and Australian Landscape Paintings’, coordinated and taught by myself, tutored by Joanne Baitz, with contributions of various length by Melissa Harpley, the curator of the exhibition, Dr Peter John Brownlee, the Foundational Curator of the Terra Foundation for American Art and the co-instigator of the exhibition with myself, and Professors Kenneth Haltman and Rachael Z. DeLue of the Universities of Oklahoma and Princeton respectively. I also convened an international symposium which took place at the Art Gallery of Western Australia in September with papers by Professor David Peters Corbett (Courtauld Institute, London and University of East Anglia), Associate Professor Rachael Z. DeLue (Princeton University), Associate Professor David Hansen (Australian National University), Professor Kenneth Haltman (University of Oklahoma), Christopher Pease (Western Australian artist), Dr Ruth Pullin (Independent Scholar), Emeritus Professor Richard Read, Symposium Convener (The University of Western Australia) and Professor Catherine Speck (The University of Adelaide). The exhibition and events were a three-way collaboration between the Art Gallery of Western Australia, The University of Western Australia and the Terra Foundation for American Art, who generously funded them all.

What emotions do they produce, and how does understanding their historical meanings change them? The editor perhaps expected this post to be a digest of the exhibition, but I won’t get beyond the first few paintings. Research surveys have established that public gallery goers average only a few seconds in front of any given exhibit, but these paintings were made to spend a lifetime with and yield their meanings and emotions slowly. I hope this series of ‘Continental Shift’ blogs will introduce themes that help visitors to engage with other paintings in the exhibition. Not that the emotional impact of first impressions don’t matter. They take time to reconstitute, like hauling back the fish that got away, a predatory theme that suits this show. Still more meaning accrues – and is lost – in the rift between their time and ours; meanings of which the original artists and viewers, of course, could not be conscious. Now that the dust has settled after more than 60 teaching and symposium hours, it’s interesting to look at them again. I am surprised by the sudden reassertion of the sheer mute look of them. I’m ready for afterthoughts from the compost of reading and discussion.

The first wall to confront us in the gallery only has room for two paintings. So there were two choices: to choose a pair that represents each country or to illustrate instead the twin themes of the show – wilderness and colonisation? This was the title given to teaching units and an international symposium designed to study the visual representation of that great clearing of the land across the globe that the eighteenth century bequeathed to the nineteenth in preparing us for the dismal era of the Anthropocence. The curator went for the latter option: the struggle between man and nature. Thus, we do not encounter an Australian painting until the fourth exhibit in a sequence running clockwise, in chronological order and alternating between countries, in this, a single chamber of what used to be the old Perth Police Courts.

The painting on the left of the opening pair depicts American wilderness: Thomas Doughty’s In the Adirondaks, c.1822–1830. It represents a rowing boat and a sailing yacht on a silvery lake surrounded by an unbroken expanse of bluish mountain forests. On the right, by contrast, is American colonisation: William Groombridge’s View of a Manor House on the Harlem River, New York, 1797. This is the only painting that dips its foot into the eighteenth century, distinguished from the later works by the stolid presence of its four-square frame. Looking north or north-east from the tip of upper Manhattan island, pasture lands recede to the manor house on the left and, at the centre, a cluster of houses and fields taper along the Harlem River, which slides behind them to the right. On the far side of the river verdant hillsides recede towards the horizon, pricked by a distant church steeple signifying further settlement. The picture constantly returns us to its most gorgeous effect: the splay of fair-weather clouds triumphantly irradiated by the pink light of sunset streaming diagonally upwards from the right. It is a trope of auspicious futurity, freedom and release above the ordered settlement where smoke drifts gently from the occasional chimney pot in the opposite direction. The weather must be cold as well as fair.

Certainly, the central focus of the scene is not the mansion of the title cropped on the far left but the cluster of fields, houses and outhouses. The houses are ridge-roofed and mostly double storey, but of variable size. Most are taller than they are long but the largest are wide and only have windows on the upper level. Is livestock or farm equipment stored beneath? They taper on a horizontal strip near the water’s edge but it is difficult to estimate from their size how far they recede in depth on the right. A local would know, and the painting was made for locals. I won’t pretend to know whether these buildings, as Denis Cosgrove writes of early American settlements, ‘refer back to European antecedents – barns, fences, farmhouse types… in a promiscuous mixing of European styles and an overall simplification which, if materially comfortable, offered to sophisticated European eyes a rude and unfinished prospect’[1] – but I suspect so.

But observe the fallacy of dividing the subjects of these paintings into ‘wild’ and ‘colonised’ too starkly. So unspoilt are the forests of the Adirondaks that there is almost a featureless redundancy about them in Doughty’s painting. The calm weather and pair of recreational boats have reduced sublimity to unthreatening proportions. This is not a Salvator Rosa. Human habitation cannot be far away. (There is a measure used in American national parks today called ‘the wilderness effect’ that determines how much wildness visitors can be exposed to before they are endangered.) Even the transition from forest to lake is graduated by boulders of human scale diminishing in size as they enter the water. Like most of the sublimity of the Eastern States, of which writers like Henry Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson would write, this scenery does not possess the tremendous and awe-inspiring quality of the Grand Canyon or Yellowstone Park. However, the third painting in the exhibition, Thomas Cole’s rendition of James Fennimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans depicts a more threatening wilderness effect based on the Hudson River area.

In Doughty’s painting, a fisherman stands in blood red trousers (to which our visiting lecturer, Kenneth Haltman, brought his wonderful erudition on predation to bear). His rod is a fashioned version of the jagged skeletons of dead trees whose branches stab the sky to the left of the lake. As he balances himself, his rod curves with tension from a taut fishing line. The rocking boat sends out concentric circles that break the surface tension of the steady lake. He’s caught a fish! That, and the sailing yacht in the distance, is the only sign of human drama, but they endow the scene with an extractive connotation and a promise of future settlement that I shall expand on in due course.

Thus turning back to other painting, we see that Groombridge’s settlement scene cannot be extricated from its defining opposite any more than Doughty’s wilderness scene can. The view is framed by rougher terrain in the foreground. The abrupt hillock disfigured by erosion and cropped on the right is a sharp reminder of the similar repoussoir that leads the eye across and into such Dutch-inspired paintings as Thomas Gainsborough’s Landscape with a Wood, Cornard, 1750 (held by National Galleries Scotland; recently displayed at the Art Gallery of New South Wales). Groombridge interpolates us looking onto civilisation from the perspective of wilderness. From terrain that is rougher than arable land, the prospect of ordered settlement unfolds on either side of a wide road that curves through fenced fields towards trim houses and outhouses and back to wilderness in the distance again. And, as with Doughty’s unsettled lake, oblique violence attends the spectator’s optical entrance into compositional space, for in William Dunlap’s account of the genesis of the painting, the artist is reported as saying: ‘I will dash a watermelon to pieces, and make a foreground of it’.[2]

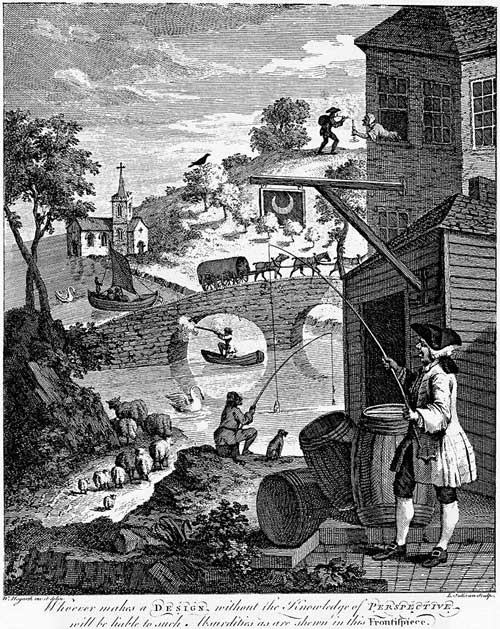

I shall stay with the Groombridge for a while longer because its anomalies help to establish a larger ideological framework for the problems of representing newly occupied lands that helps to define their emotional effect and purpose. None of our visiting lecturers claimed to be experts on Groombridge’s work, but neither had they seen anything quite like it in American collections. We all remarked on its relative gaucheness: the shapeless mess of the foreground boulder (compared with Doughty’s graduated stepping stones); the fanciful twirls of foliage – like doodles in faded brown blood – on the foreground hillock; the clumsy wide angle at which a mysterious built structure is set across the foreground to the left, sealing off settlement from wilderness. Is it a wall or some kind of building? Is it made of stone or wood? What is its scale? Why is it doubled? One would simply have to know what it is. The wonky mansion in the middle distance, sunk in another expanse of bare earth like a railway siding (but rhyming with the natural) erosion of the hillock on the left), is worthy of Hogarth’s Satire on False Perspective.

It barely stands up. Yet for all its faults, the painting conveys a common sociality and expansive freedom, culminating in the joyous transcendence of the soaring pink sunset. It produces beauty from incompetence that repeatedly delights. My heart leaps time and again when I see that sky from any distance in the gallery and makes me wonder from what distance and in what building it was originally intended to be seen. The effect has something to do with the minutiae of everyday humanity sanctified by natural grandeur and finite order shot through with infinity: the dialogue between settlement and wilderness in another key.

The drawback of ‘great’ paintings is that you can’t recognise a visual problem once it’s been solved. Everyone relished this painting’s curious oddities and anomalies. But it might also be addressing an ideological problem of the utmost importance for colonial endeavour. The problem is arguably concentrated in the bent form of the farmworker who trudges from left to right with his lower half occluded by the rough terrain of the rising foreground, that margin between settlement and wilderness again. So what is the problem of painting new lands that these and most of the other paintings in the show attempt to resolve in their various ways? We earn more impact points if you read the answer in the next thrilling instalment….

Emeritus Professor Richard Read is a full term Associate Investigator with CHE, and a Senior Honorary Research Fellow at The University of Western Australia. He was formerly Winthrop Professor in Art History in the Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Art at UWA, and has published in major journals on the relationship between literature and the visual arts, nineteenth- and twentieth-century European and Australian art history, contemporary film, popular culture and complex images in global contexts.

[1] Denis E. Cosgrove, Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape (London Sydney: Croom Helm, 1984), p. 170.

[2] William Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States (1834; reprint ed. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1969), vol. 2, pt. 1, pp. 47-48.